Uluqsaqtuua (Holman Island) Printmaking

Uluqsaqtuua (Holman Island) is situated on the western side of Victoria Island, 925 kilometres north of Yellowknife. Holman and Cambridge Bay are the island’s main settlements.

Uluqsaqtuua means ‘where there is copper’ in Inuktitut. Today’s residents are descendants of the Copper Inuit who, in turn, are thought to be descendants of a group from the Thule people who arrived in the copper-rich area around 1,000 AD.

Copper Inuit were named such by the English because of the copper tools they fashioned and the copper artifacts used by their ancestors. The Inuit call themselves the Ulukhaktokmiut meaning “the place where ulu parts are found”. (An ulu is a crescent-shaped knife used most often by Inuit women.)

The English name for Uluqsaqtuua, Holman Island, was given in honour of J.R. Holman, a member of the Inglefield Expedition of 1853. (Sir Edward Augustus Inglefield (1820 – 1894) was a Royal Naval officer who led one of the searches for the missing Arctic explorer John Franklin during the 1850s. While he did not find Franklin, his expedition charted previously unexplored areas along the northern Canadian coastline, including Baffin Bay, Smith Sound and Lancaster Sound.)

The arrival of European explorers in the area in the 1800s created an economy based on trapping, hunting and trading for the nomadic Inuit. However, into the 20th century and a shrinking market for furs, hunting and trapping could no longer be solely relied upon for income. Similarly throughout the Arctic, the Ulukhaktokmiut were required to find other sources of income, which has come in the form of jobs connected to either municipal or territorial government and some employment in oil, gas and diamond exploration.

Additionally, art has provided a viable alternative to both the traditional way of living and the government and industry-created jobs. In specific, Holman is known for its successful printmaking economy.

Printmaking

Printmaking does not have a direct traditional base in Inuit culture. In fact, the Inuit do not have a word for art. The objects they made always had a functional purpose and were not created for the sake of art.

Aspects of traditional Inuit culture are however conducive to modern printmaking techniques and themes. It has been suggested that the incised carvings on bone or antler, women’s facial tattoo marks, or inlay skin work on clothing, mitts and footwear set a precedent in terms of techniques and approach to design that the Inuit could draw upon for their drawings and printmaking. The Inuit were also not exposed to paper and drawing utensils until contact with Europeans, but the principles of design and execution in making traditional objects were transferable to modern printmaking techniques. For example, the first stencils in Holman were made from sealskin.

Mirroring the cooperative nature of Inuit society, early printmaking in the North was also a cooperative process. In the beginning of the process drawings would be brought to the co-operative and the artist would be paid for their work. Images selected for reproduction in the print collection are transferred to the print format by another artist. And it is possible that a third individual would then print the image onto paper. A completely cooperative process.

The late Reverand Henri Tardy, an Oblate priest, who was responsible for introducing printmaking to Holman in 1939, made the following comments about his experience:

In those early years I sensed an artistic potential in the people of Holman. There was the germ of it in their imaginative story telling, their artful mimicry and the creative decoration of their clothing.

The Holman Co-operative is living proof that necessity is often the mother of invention. … ten of us scraped together ten dollars each to help start some modest work in stone carving and decoratively sewn seal skin. That was the beginning.

When we decided to try printmaking, the only technique we knew anything about was stencil-cut, using sealskin. The first stencil was thus cut in sealskin and the first print was made using fine screening and a toothbrush dipped in ink…we produced ten prints [with this method].

A Cape Dorset print seen at a friend’s house launched the Co-operative on a long, often difficult evolution which has made our village an independent, united community with pride in its traditional values and renown [sic] for its graphic art and superb needlework.

To help sell the prints Father Tardy and a group of artists formed the Holman Eskimo Co-operative in the early 1960s and released its first set of prints in 1965. Holman has the distinction of being the only community in the western Arctic with a printmaking program.

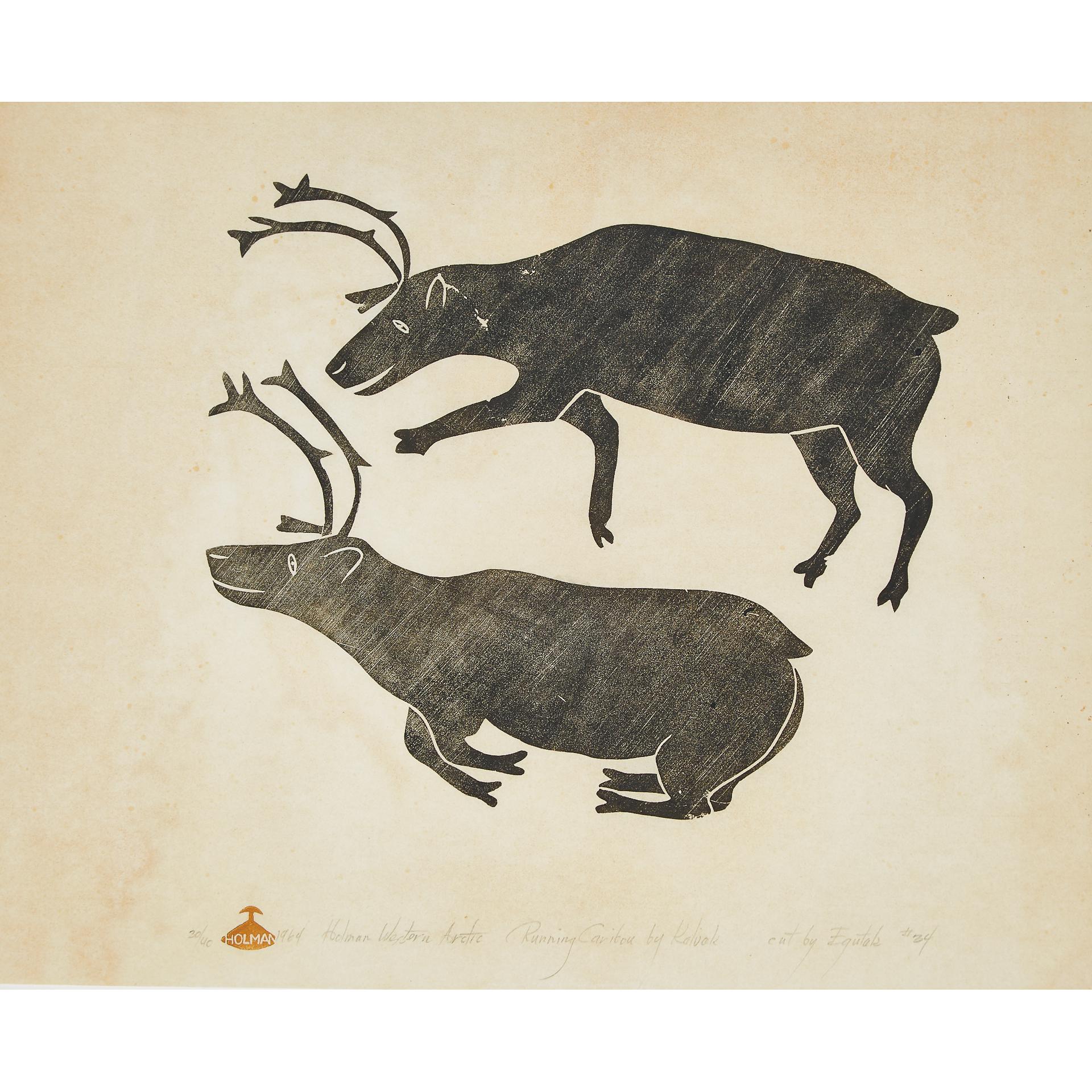

The early printmaking equipment in Holman’s was simple and the resulting printed images were basic. They were characterized by simple black silhouettes created from pencil drawings. Sometimes the prints would match black with one deep colour depicting an image with a very sharp edge that drew from the stone block’s own edge to outline the image. Early prints showed themes of shamans, ceremonial dancers, figures from legend, and illustrations of everyday life.

Over the past 40 years Holman printmakers have used several techniques for their printmaking: stone cut, stenciling on seal skin, mylar and wax paper, lithography, woodblocks and acid free etching.

The stonecut method of printmaking fell out of favour with Holman artists, as the dust the process created was a health risk. Woodblock printing replaced it temporarily. The images this technique produced were considered cartoon-like by buyers in the South and its use declined.

As of 1986 stenciling and lithography have been mainstay techniques of Holman artists. In the beginning stenciling was done on seal skin, then wax paper and now mylar is used. Stenciling, when using mylar, is considered to be a very precise technique that allows the artists to create a three-dimensional quality. The Holman style has been described as minimalist, with few details, using images that originate from their Copper Inuit traditions.

Today’s prints are made in editions of 50 and can be recognized by an ulu marked with the word ‘Holman’ on it.

Sources:

IAQ, Fall, 1989, V4. No.4

www.canadiangeographic.ca/magazine/ma05/mosaic.asp

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

www.nnsl.com/frames/newspapers/2005-10/oct31_05na.html

www.assembly.gov.nt.ca/visitorInfo

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

www.ccca.ca/inuit/english/holman.html

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

www.assembly.gov.nt.ca/visitorInfo

www.assembly.gov.nt.ca/visitorInfo

www.nwt-tno.inac-ainc.gc.ca/mpf/communit/com_e.asp?ID

IAQ, Fall, 1989, V4. No.4

www.canadiangeographic.ca/magazine/ma05/mosaic.asp

www.beaufortdeltaedu.nt.ca/bsite/holman/town.htm

www.nwt-tno.inac-ainc.gc.ca/mpf/communit/com_e.asp?ID

IAQ, Fall, 1989, V4. No.4

IAQ, Fall, 1989, V4. No.4

IAQ, Fall, 1989, V4. No.4

www.canadiangeographic.ca/magazine/ma05/mosaic.asp